The following is an account of European encounter with the indigenous inhabitants of Appin. This article was submitted to and published by the Macarthur Advertiser (with slight changes) on 22 August, 2001. Campbelltown and Airds Historical Society published a paper entitled “Speculations on the Appin Aborigine Massacre” by Peter Mylrea in its journal “Grist Mills” Vol. 13 No. 3, December 2000.

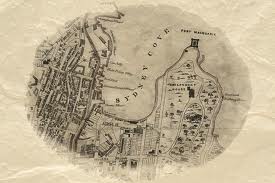

When Governor Macquarie and his wife visited the Cowpastures in 1810, they were welcomed by “two or three small parties of the Cowpastures natives” who performed “an extraordinary sort of dance”. Yet within a few short years, orders issued by Macquarie would result in the deaths of more than fourteen Aborigines. When Europeans took up land grants, they cleared and fenced the land, irrecoverably changing the patterns of hunting and gathering that had been followed by the Dharawal people for tens of thousands of years. Some European settlers formed a close rapport with Aborigines. Charles Throsby of Glenfield was accompanied by Dharawal men when he explored the southern highlands area. Throsby was a persistent critic of European treatment of the Aborigines. Hamilton Hume who, in 1814 with his brother John, made the first of a number of long exploratory trips southwards, did so in company with a young Aboriginal friend named Doual. Whereas the “mountain natives” (probably Gandangara) had a reputation of being hostile in defence of their people and their land, the Dharawal were peaceful and had no history of aggression. Unfortunately few settlers could distinguish between the two groups. In 1814, Macquarie issued an order in the Sydney Gazette, admonishing settlers in the Appin and Cowpastures area. “Any person who may be found to have treated them [natives] with inhumanity or cruelty, will be punished?.” This followed an atrocity when an Aboriginal woman and her children were murdered at Appin. Two years later, in the drought of 1816, the Gandangara came again from the mountains in search of food. Europeans were killed and about 40 farmers armed themselves with muskets and pitchforks. Macquarie ordered Captain Schaw to lead a punitive expedition against the “hostile natives” in the regions of the Nepean, Grose and Hawkesbury rivers. Lieutenant Charles Dawe was ordered to do the same proceeding to the Cowpastures. Captain John Wallis had similar orders and was to march from Liverpool to the Districts of Airds and Appin. Wallis’s guides were John Warby and two Dharawal men, Budbury and Bundle. Warby had explored the Cowpastures, the Burragorang Valley and Bargo area, establishing a close working relationship with the Dharawal. A list of the names of the supposedly “hostile natives” was provided by Macquarie. All Aborigines encountered by the military were to be made prisoners. In the event of their refusing, they were to be fired up and any “native” men killed were to be hanged on trees in conspicuous parts of the country where they fell. Budbury and Bundle were both unwilling guides, and Warby likewise showed his distaste for the military operation by saying he would take no responsibility for the Dharawal men. The following night Warby “winked at the escape of Bundle and Budbury”. “I was exceedingly annoyed” wrote Captain Wallis. The next day (April 12) a number of Aborigines came forward unarmed, but the names of two (Yallaman and Battagalie) were found to be on the wanted list. Settlers named Kennedy and Hume quickly reassured Captain Wallis that Yallaman and Battagalie were harmless and innocent. Hume even lied, claiming he had seen the Governor erase their names from the “wanted” list. On april 13 Warby disappeared. Suspicion lingers that he may in fact have set off to warn the Dharawal. Warby reappeared the following day, but was still uncooperative. v Word came from McAllister, an overseer on Dr Redfern’s farm, that a group of Aborigines were camped there, so the soldiers marched north along the Georges River. It was a wild goose chase. No Aborigines were sighted. “I reprobated McAllister’s conduct most highly” wrote Captain Wallis. However, on the evening of April 16 word came from Tyson; a group of Aborigines were camped at Broughton’s farm, near Appin. A little after 1 o’clock in the morning the soldiers arrived at the camp. “The fires were burning but deserted.” “A few of my men? heard a child cry”, wrote Captain Wallis. “I formed line ranks, entered and pushed on through a thick brush towards the precipitous banks of a deep rocky creek. The dogs gave the alarm and the natives fled over the cliffs? It was moonlight.” “I regret to say some (were) shot and others met their fate by rushing in despair over the precipice? Fourteen dead bodies were counted in different directions?.” How many others might have died when they plunged over the precipice will never be known. Five prisoners were taken. One was Hume’s friend, Doual. In August 1816, Macquarie banished Doual to Van Diemen’s Land “in remittance of the death sentence imposed upon him”. Macquarie had started out as a sympathetic friend to the Aborigines. In the end, more than fourteen (including women and children) met violent deaths as a result of his orders. The date of the infamous massacre at Appin was 17th April 1816.